A Call to Arms Against Banned Books

As a lawyer, who is also a writer and creator of The Writer’s Law School, I sometimes believe my superpower lies in spotlighting legal issues that simmer beneath the surface. For instance, underneath the proliferation of book banning sweeping throughout the country is the threat to one of the most esteemed amendments of the U.S. Constitution—the First Amendment. As a brief reminder, the First Amendment guarantees the freedoms of religion, expression, assembly and the right to petition.

You know the situation is growing desperate when classic novels like “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee, “The Handmaiden’s Tale” by Margaret Atwood, “Huckleberry Finn” by Mark Twain, “The Bluest Eyes” by Toni Morrison, “Maus” by Art Spiegelman, “Between the World and Me” by Ta-Neshi Coates and “The Hate U Give” by Angie Thomas are under attack. Add to that list “Outlander” by Diana Gabaldon and George M. Johnson’s “All Boys Aren’t Blue.”

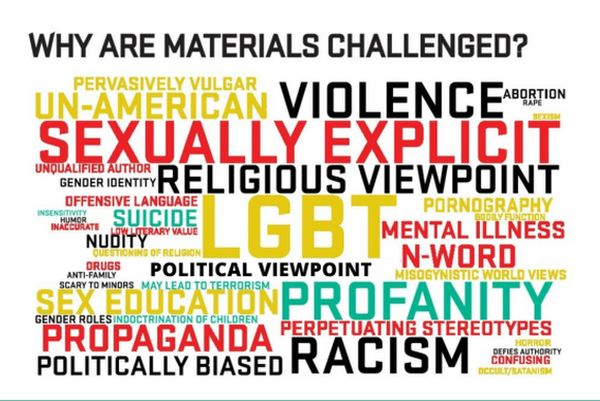

The question is whether school districts can legally remove these masterpieces from their libraries? The answer is not as clear as the school administrations would like to believe. In 1982, the Supreme Court decided in Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District No.26 vs. Pico (457 U.S. 853) that the First Amendment imposes limitations on a school board’s exercising its discretion in removing books from junior and high school libraries. Local school boards may not remove books simply because they dislike the ideas contained within those books, nor can they seek by their removal to prescribe what shall be the governing positions in politics, nationalism, religion or other matters of opinion. In other words, the school board cannot censor political or social ideas contained with those books.

Contrary to the forty-year constitutional precedent, the recent trend in some parts of the country has been to ban books based on sexual and racial identity. In states like Oklahoma, they introduced a bill in the State Senate seeking to prohibit public school libraries from stocking books that discuss sexual identity, sexual activity or gender identity. Of course, we are all aware of Florida’s controversial “Parental Rights in Education Act” aka “Don’t Say Gay” bill, which limits what classrooms can teach about sexual orientation and gender identity. Wyoming, Tennessee, Virginia, South Carolina, and Mississippi appear poised to jump on the censorship bandwagon.

What does this mean for writers? Are we to stifle our creative juices and not tell the stories we want to tell or write about the characters we desire to explore because we are afraid of being banned? What about the chilling effect censorship has on the audience? Should readers be shamed because of who they are; should they be barred from reading about people who represent their communities?

My new crime thriller, HOOKER AVENUE, involves two female protagonists, a cop and an attorney, who are thrust into the path of a serial killer when the attorney saves a mysterious woman from drowning. Jessie Martin is a single mom attorney, whose estranged friend, bi-racial Detective Ebony Jones, is investigating a series of cold cases involving missing prostitutes. The near-drowning victim, Lissie Sexton, is a young, unwed mother, sex worker and addict who has lost custody of her son to her parents. Ebony believes that Lissie is the key to unlocking the serial vanishings, while Jessie faces professional ethical dilemmas as she navigates whether to protect her client, Lissie, or assist Ebony in her investigation.

Viewed through the lens of racial discrimination and conservative sexual attitudes, HOOKER AVENUE could be ripe for banning. It checks all the boxes: unwed mothers, prostitution, drug addiction, serial killings, a Jewish protagonist and a bi-racial protagonist. If you consider your own work through this distorted perception, it’s easy to see how a less diverse, open mind can twist your story to fit their profile for banning.

If “The 1619 Project,” by Nikole Hannah-Jones, a bestseller about slavery in America, can become the most targeted book in America, then it is easy to imagine that we can all suffer such a fate.

According to a recent Harvard University study, students spend twenty percent of their time in school. The content of school time should reflect the rest of their world, not someone else’s political agenda. Children should be as free to engage in uncensored reading as they do in engaging in social media and social activities. As writers, parents, and readers, we have an obligation to protect our First Amendment rights for future generations. The books our children read should not be weaponized or become political footballs. We learn about ourselves through what we read, and a more diverse, inclusive reading list encourages a more educated, equitable, and inclusive society.

What action can writers take? We should not wait until the battle has advanced to the point of no return, limiting our student’s rights to free access to books and knowledge. Report censorship to the American Library Association. They are strong advocates for protecting books from censorship, maintain a database of incidents and challenged materials (330 reported last fall), and supply librarians with materials necessary to address censorship issues. For more information, visit https://www.ala.org/advocacy/bbooks.

The Authors Guild is another resource for advocacy on free speech, by encouraging a National Letter-Writing Campaign to school boards, lawmakers and newspapers, and maintaining the Freedom of Expression watch list. They recently launched a Banned Books Club, a #unitedagainstbannedbooks campaign, and www.unitedagainstbannedbooks.org. For more information on combating censorship, visit www.authorsguild.org.

As you can tell, this issue disturbs both the lawyer and the writer inside me. Book banning is an attack on our livelihood and our sensibilities. I hope this essay will energize you to take action on this attack on the First Amendment, along with other recent attempts to thwart our constitutional rights and case precedents. If we are told what we can’t read, or told what we can’t do with our bodies, then Bradbury’s “Fahrenheit 451” and Atwood’s “The Handmaiden’s Tale” have transmuted from fiction to reality.

You may not have my legal superpower, but together as writers, we possess the power to protect our constitutional rights.